Clara Tice Rediscovered

by Patricia Guenter

Clara Tice (1888-1973), once known as the “Queen of Greenwich Village,” is nowadays almost forgotten. So who was she and why was she called the “Queen of Greenwich Village”?

Clara Tice grew up together with her younger sister Sarah, her older brother Clifford, her mother Mary and her father Benjamin in New York City, where her father worked for the Children’s Aid Society. Interviewing herself for the St. Louis Star Tice recalled that she had always been drawing with the support of her parents - which was quite exceptional at that time since parents normally preferred their offspring to have jobs which are more lucrative and respected. After having done the “usual work at school without exciting any great amount of comment,” Tice was able to study under Robert Henri.

Henri, one of the founders of the “Ashcan School,” which caused quite a stir in its beginning, was a well-known artist as well as an influential teacher. Recognizing Tice’s unique style, Henri not only helped her to perfect her technique but also told her – as well as his other students – not to care about rejections. “The better or more personal you are the less likely they [your works] are of acceptance. . . .you are painting for yourself, not for the jury,” were his words. Thus also criticizing the established jury system, Henri organized together with some colleagues - e. g. John Sloan and William Glackens - and some of his students, among them Tice (who also backed the endeavor financially) the first exhibition of Independent Artists. The show opened on April 1, 1910 and attracted with its revolutionary “no jury, no awards” concept a crowd of over two thousand people on the opening night. Despite such a large audience only three artworks were sold that night: one drawing by Henri, one picture by Tice and a sketch by Edith Haworth. This exhibition was not only the first time that several of Tice’s works were presented to the public, but it was also an important step in her career because it meant the acknowledgement of her colleagues.

Another Henri student, who participated in this show, supported it with money and worked on the hanging, was P. Scott Stafford. It is not clear if Tice and Stafford met each other through Henri or if they knew each other before they both took Henri’s classes. Anyhow, Stafford was the man whom Tice married on June 30, 1911. Their marriage was not too successful and they thus split up soon after the wedding – without ever getting divorced.

After the turmoil of the first exhibition of Independent Artists, interest in Tice and her art decreased until it skyrocketed in mid-March 1915, when the New York Tribune reported about the “Comstock raid” on its front page. According to this newspaper, Anthony Comstock, leader of New York City’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, had gone to Polly’s – a popular bohemian restaurant in Greenwich Village where artworks by Tice were exhibited – to confiscate those because he deemed them immoral. The Tribune states that a diner bought the exhibits before Comstock was able to execute his plan, but Tice describes, in contrast to this, that some of her friends had found out that Comstock was coming and had removed the pictures from Polly’s before he arrived. It actually does not really matter what the details of this occasion are, the most important thing is that the attempted raid and the ensuing newspaper article helped to promote Tice and her art significantly.

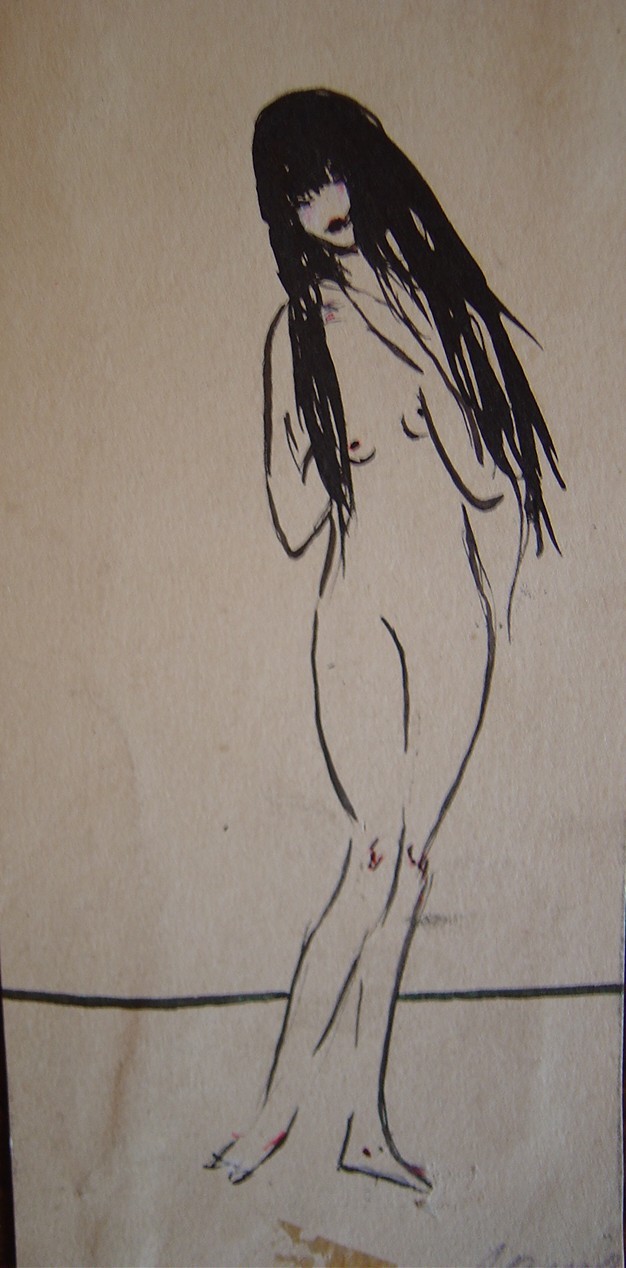

After this incident Tice’s creations, whose characteristic was the depiction of movement, could be seen in magazines such as Vanity Fair, The Quill, Rogue and Cartoons Magazine as well as in newspapers like The New York Times. The publicity caused by the “Comstock raid” also made her first one-person-exhibition a financial success. The show took place in May 1915 at Bruno’s Garret – owned by Guido Bruno, an important Greenwich Village figure – in Greenwich Village. Bruno favored Tice’s works so much that he not only showed some of them at another exhibition in 1915 but also featured them in his numerous publications. Most of the magazines and newspapers in which Tice’s artworks could be seen printed also photos of her and referred to her in articles – she was usually mentioned in connection with Greenwich Village, a downtown New York City neighborhood, which was known as the center of bohemian activities at the beginning of the 20th century – and even called her, as mentioned earlier, the “Queen of Greenwich Village.” Tice’s appearance – she was the first woman in Greenwich Village to bob her hair and often wore striking clothes; she was only about five feet tall and usually accompanied by her large Russian Wolfhound – but also her modern artworks and her acquaintance with other bohemians contributed to the fact that she was seen as a representative of downtown bohemia.

It is possible that another Greenwich Village personality, maybe Marcel Duchamp or Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, was the one who introduced Tice to Walter and Louise Arensberg. The Arensbergs, wealthy patrons of the arts, were hosts to a group of artists – among them Duchamp, Man Ray, Charles Demuth, Beatrice Wood and Tice – which came to be known as the Arensberg Circle. Between 1915 and 1921 these moderns met frequently at the Arensbergs’ uptown apartment to discuss the latest trends in art and society but also to play chess, listen to music and enjoy the food and drinks the Arensbergs served. Their most important joined project was the formation of the Society of Independent Artists and its first exhibition, which took place in 1917 and was also inspired by the “no jury, no awards” concept. The later show was even more radical than the 1910 exhibition because anyone who paid the required fees was allowed to exhibit his or her works. This idea seemed attractive to so many people that in the end more than 2,000 works – among them Tice’s artworks – were shown.

After this exhibition Tice continued working as a magazine illustrator and was busy with several Greenwich Village projects. Since she was seen as a representative of New York’s bohemian downtown, she was even asked to play herself in the Greenwich Village Follies of 1919 – which she did. One of these performances was to change her life forever. Cecil Cunningham, who also belonged to the cast and was then a well-known Broadway actress, introduced her brother “Harry” Patrick Cunningham to Tice after one of the shows. They fell in love with each other and lived together until Cunningham’s death in 1947.

Thanks to the prosperity of the 1920s this decade was also a very successful one for her. It kicked off with a one-person-exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in New York City in 1922. Her works could be seen almost exactly one year later again at the same location. She also designed an Egyptian entrance for a charity event in Brooklyn and created a mural for the New Club Caravan on 5th Avenue in Manhattan – just to mention a few projects. Her illustrations still appeared in magazines and newspaper, from 1924 on they also adorned books. Many of these images, which are printed in splendid colors which often include gold, depict nude women. To avoid censorship most of these books were privately printed by the Pierre Louÿs Society.

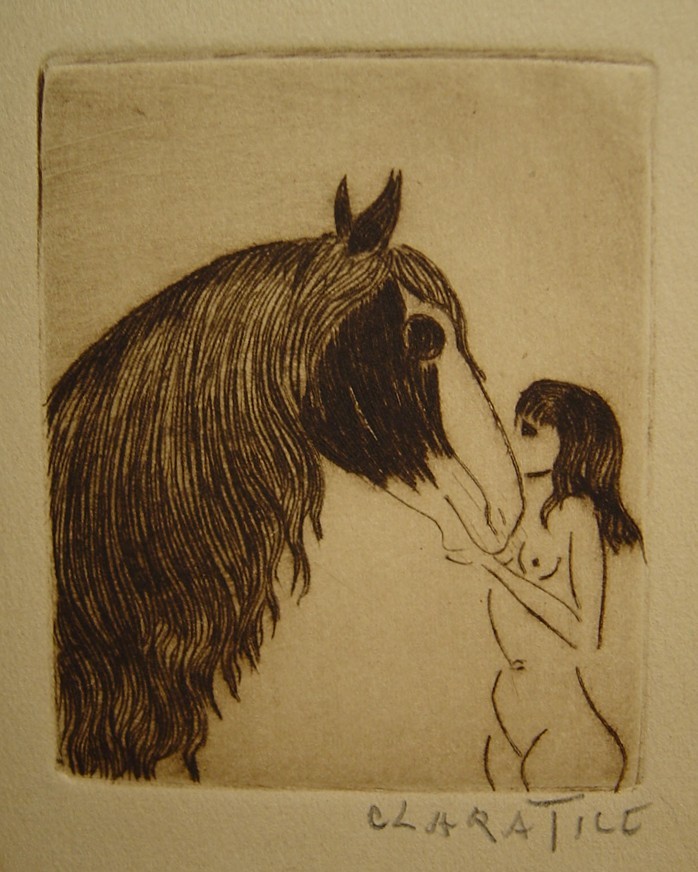

Although Tice had a few more exhibitions in New York City in the 1930s, she lived during this decade with Cunningham in Connecticut, where she was able to keep horses, dogs and other creatures. Animals and art being her two great enthusiasms. In the country she also started working on her memoirs “My Model World”, which she – unfortunately - never finished. Another project, which she completed, was her book ABC Dogs, which was first published in 1940 and is a charming children’s alphabet book. Each letter of the alphabet is accompanied by a picture of a dog whose name begins with the same letter. These images are quite a change compared to her nudes.

After Cunningham’s death in 1947, Tice returned to New York City, eventually moving to Queens in 1951, where she would stay for the rest of her life. In her small apartment she created artworks and took care of sick animals. Unfortunately, her health deteriorated, both her hands were afflicted by arthritis and she was blinded by incurable glaucoma. “Courageous and independent as ever,” she refused pleas by relatives to move in with them and lived alone in her apartment until her death on February 2, 1973.

This text is a slightly altered version of: Guenter, Patricia. “Clara Tice Rediscovered.” Clara Tice: A Dada Woman. Fwd. Anne M. Lampe. Ex. cat. Lancaster: Demuth Museum, 2007. 4-10.

All images are courtesy of Private Collections.

Last Update: January 12, 2012.